The Secret Garden: Interview with Nour Ouayda

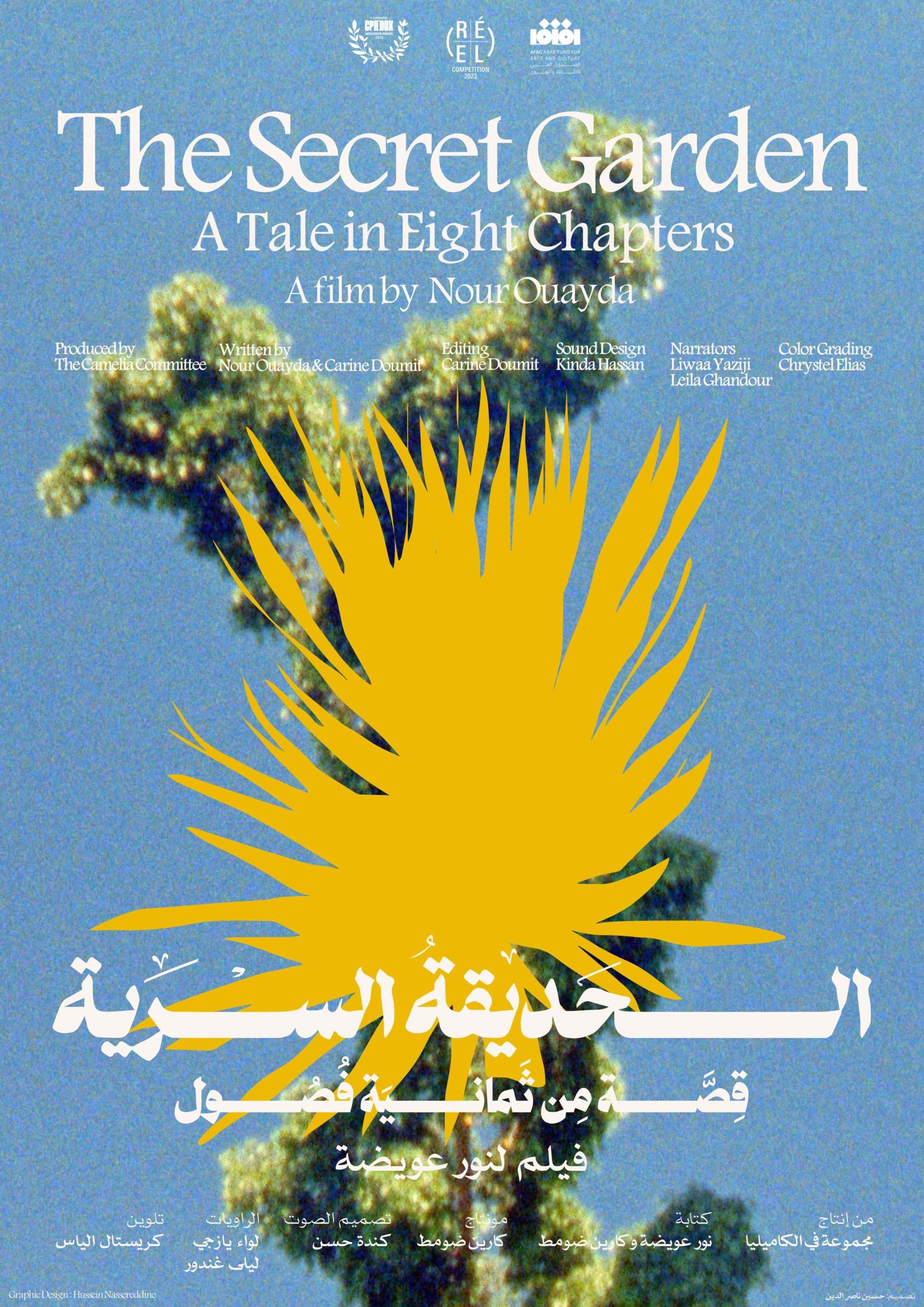

Nour Ouayda, The Secret Garden still, 2023. Courtesy of the Artist.

With text by Hind Mezaina.

The Secret Garden by Nour Ouayda is a 27 minute film told in 8 chapters about an unnamed city overrun by plants, trees and flowers. Shot in 8mm and 16mm film, the beautifully composed images of the plants evoke a sense of fear and the unknown. The film is narrated by two whispering voices, the film’s protagonists, Camelia and Nahla, who are investigating how this overnight invasion happened. The Secret Garden had its world premiere at CPH:DOX in March 2023 and since then it has screened at many other notable international film festivals. I interviewed Nour Ouayda about the making of the film.

Hind Mezaina: Lately, I’ve been seeing a growing interest by artists and filmmakers in analogue photography and filmmaking. What drew you to shoot on film?

Nour Ouayda: I shot the film on Super 8 and 16mm, with cameras that allowed for in-camera editing. It was a way to play around with instinctive methods of filming and to improvise based on body movement, breath, rhythm and presence in the spaces I was filming.

This was very important for me as it was a way to transfer the energy of a certain place onto the film, especially since the relationship to place was at the heart of the film. When we started editing, certain sequences were already there and were used as is, like the palm tree sequence for instance where I alternate between various time-lapse speeds, which gives this contrasting effect of a smooth traveling intercut with bursts of frenetic energy.

In camera-editing is something I also worked with in two videos I made with my smartphone in 2020 and 2022. It's not the exact same technique as when I am shooting with film cameras, but it’s just a way to say that I am drawn to equipment that allows this kind of improvisation and instinct.

On another hand, there’s also a certain quality to images shot on film, they feel a bit less immediate, as if they belonged to another time - and this works really well with the fairytale and fantastical tone of the film.

HM: You learn more about a city when you walk, it allows you to observe it in a more intimate way. What was your process when it came to finding plants and their locations?

NO: The original idea for this film came about when I started to see plants around the city that I had never noticed before. As soon as I noticed them, I could not unsee them. I became obsessed and spent a lot of my time looking at them. And the more I looked for them or looked at them, the stranger they appeared.

As I navigated across the city to go to work, or to go out, I kept an eye out for the plants that surrounded me. This would happen when I walked as well as when I drove.

When I found plants that caught my attention, with interesting shapes, forms, colours and also in interesting locations, I would take pictures with my phone. If I noticed them whilst driving, I’d stop my car, photograph them, and note down the location.

As for observing a city in an intimate way when walking, I think for me, the intimacy comes with the close-up shot. The intimacy emerges when I stare at the details, I look so closely that the closeness becomes uncomfortable and overwhelming.

When I started to film, I had two rules: 1) to go out and film in one location and expose only one roll of film, which is around 2 minutes 30 seconds for Super 8 film and around 3 minutes for 16mm, 2) everything I shot had to be located within the city limits of Beirut. So it's very little filming each time. It was really concentrated around a specific location and the plants that inhabited it. I tried to find as many variations of plants and locations as possible: plants located close to the water or growing out of a block of concrete, plants that were small and close to the ground, and others that were high up on buildings or big trees. I wanted to create a feeling that it was an invasion of multiple plant species, that we're talking about a whole complex living system that is invading the city.

HM: How did you come up with the fairytale-like text and what was the writing process like?

NO: I wrote the film with my collaborator Carine Doumit who is a writer and editor. She also edited this film. The fairytale-like tone was a combination of trying to position the film in a time that is different from ours, a time that fairy tales and myths belong to, and to bring out the strangeness and the eeriness that we knew the images contained. Of course, when I'm talking about fairy tales, I'm also talking about myths and about the fantastical. The text takes inspiration from the literary genre of magical realism in which magical elements are treated as a natural part of the story's environment. It is a universe in which fantasy slips into everyday life.

I already had the premise of a plant invasion following a mysterious explosion before I started to shoot. It guided my choices when filming but also was a very vague framework that allowed for experimentation. Carine accompanied the shooting through continuous discussion and never saw any of the images until I had finished gathering them and we were ready to start editing. The writing started with the editing. We were editing and writing at the same time. For example, the idea for the chapters came from the way in which we viewed the rushes: we classified them. For example, plants that looked domesticated, plants that looked alien, the ones that looked wild, plants at night, plants during the day, and so on.

HM: You don’t explicitly indicate the location of the city, but I couldn’t help think how the film touches upon a city’s trauma, Beirut to be more specific, and its impact on the people living in it.

NO: The film is about the transformation of a place after a disruptive event. It is about how a place transforms in the aftermath of an event that disrupts the course of things. In the film, a voice calls it: “an event that might change the course of things to no return”. What is this point of no return?

Of course, the film is related to Beirut, due to the fact that I shot the film in Beirut, a city I have lived in in all of my life. So it is a film that came out of a place that is marked by a multitude sequence of disruptive events that reshuffle each time our understanding of reality and of the real. It was important for the film to carry traces of these violent changes without directly referencing one of them. In relation to your first question, it was for me a matter of using cameras and machines that could pick up on the vibrations of a certain place and register them onto the images themselves.

HM: Plants are signs of life, even hope, but in your film they are mysterious and suspicious.

NO: When writing this film, it was important for Carine and me not to fall into this dichotomy of man versus nature, of control versus wilderness. We wanted to blur the lines, to describe plants that gave us a feeling of comfort and danger at the same. And I like that plants are both, as nature is indeed dangerous. This is something that I explored in my previous film, one sea, 10 seas (2019) where I tried to show the multiple faces of the sea, which can be both a rejuvenating water element and a monstrous deadly creature.

I guess this circles back to the idea of familiarity and unfamiliarity, and trying to see how in this time of great change familiar things become unfamiliar. How and when do things that are generally supposed to comfort us become sources of anxiety, and vice versa?

Nour Ouayda is a filmmaker and film programmer. Her films experiment with various forms of fiction writing in cinema. She is a member of The Camelia Committee with Carine Doumit and Mira Adoumier and part of the editorial committee of the Montreal-based online film journal Hors Champ. Between 2018 and 2023, she was deputy director at Metropolis Cinema Association in Beirut where she managed and developed the Cinematheque Beirut project.

Previous films:

Towards the Sun (2019, 17')

one sea, 10 seas (2019, 42')

I was grateful the camera tore out my camera's microphone (2020, 5')

Not all things that shine are beautiful (2022, 5')