A Tap at the End: مياه صالحة, Water Ethics, and the Saudi Pavilion at the 2025 London Design Biennale

All images of GOOD WATER at the Saudi Pavillion (c) Daveeda Shaheen 2025

The Saudi Pavilion’s contribution this year, Good Water, makes a gentle but insistent demand. It borrows from the familiar and repositions it just enough to unsettle. Its title, though direct, belies the complexity of the work — a meditation on passive consumption, ethical design, and infrastructural inequity, running through a seemingly innocuous resource. We — Alaa Tarabzouni, Dur Kattan, Fahad bin Naif, Aziz Jamal, and I — conducted the interview in the central lobby of Somerset House, a transient space of footsteps and shifting voices, made momentarily our own. It was Press morning, and the building was relatively empty, save for a few lively conversations drifting from neighboring pavilions. I was encouraged to engage with the installation first — to take a moment, walk slowly around the Sabeel, notice the flow of water.

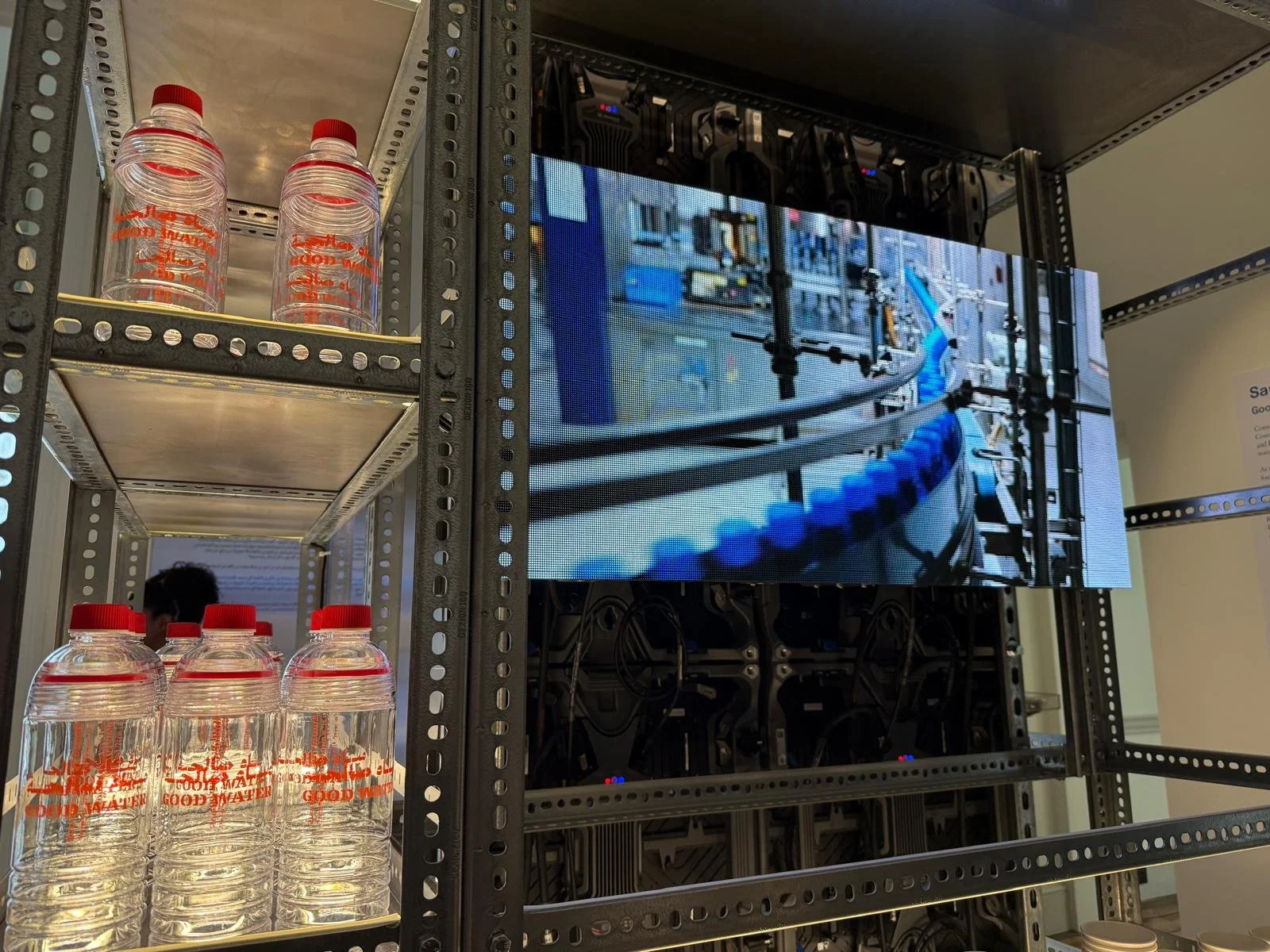

The installation asked nothing of me, and yet it did. It was as unassuming as it was deliberate: a skeletal form, modest taps, compostable cups, and what looked like plastic red-capped bottles, stacked just shy of convenience. A handful of industrial looking tomes lightly stacked on the bottom shelf brimmed with poetry and photography: archival, academic, admonitory. One of the four designers, Jamal, was not present, but his ideas ran through the conversation. I was the first to speak with the design team in full that morning. I had to raise my voice above the ambient clatter to be heard. After the interview, we stepped back outside. It had begun to drizzle and we were flanked with grayness. Kattan glanced up and quipped, “This is bad water!” Everyone laughed. It was a small moment — one of those offhand jokes that lands because it touches something precise — and then we scattered back into the pavilion.

Dalia Hashim: Can we start with the naming? The choice of “Good Water” is almost childlike in its simplicity. What is it that makes water "good"? Is it a reference to moral value, potability, or perhaps to public versus private access?

Alaa Tarabzouni: The name first came about in Arabic (مياه صالحة) — Miyah Saleha — meaning potable water. But with the complexity of access to water and making water potable, the real question became one of the morality and ethics of water usage, especially passive versus active use. Drinking is active, but we wanted to highlight that 500ml, the size of our bottles, is also the equivalent of one AI prompt. It's about awareness of one’s water footprint. There’s a lot of talk about carbon footprints, but water feels distant because its consumption doesn’t feel active. The pavilion name asks a moral question.

DH: It's certainly a provocative question. Is it perhaps a quiet indictment of how we interact with water?

AT: I don’t think so. It’s unavoidable — water is in everything: jeans, apples, meat. Agriculture is the largest consumer, followed by general industry. There’s no judgment, just awareness.

DH: Let’s speak about the Sabeel. It transforms a symbol of hospitality in Arab culture into a critical apparatus to interrogate resource politics. In placing this behemoth structure within Somerset House, how do you navigate the tension between heritage or cultural signifier (that is, Somerset House) and contemporary critique? And how does this spatial intervention speak to the Biennale’s theme, Surface Reflections, in the context of infrastructural inequities?

Fahad bin Naif: I feel it’s the juxtaposition. The Sabeel is a design without a designer, embedded in Saudi urban fabric, now placed against Somerset House’s neoclassical backdrop. It’s at once jarring and rich in contrast.

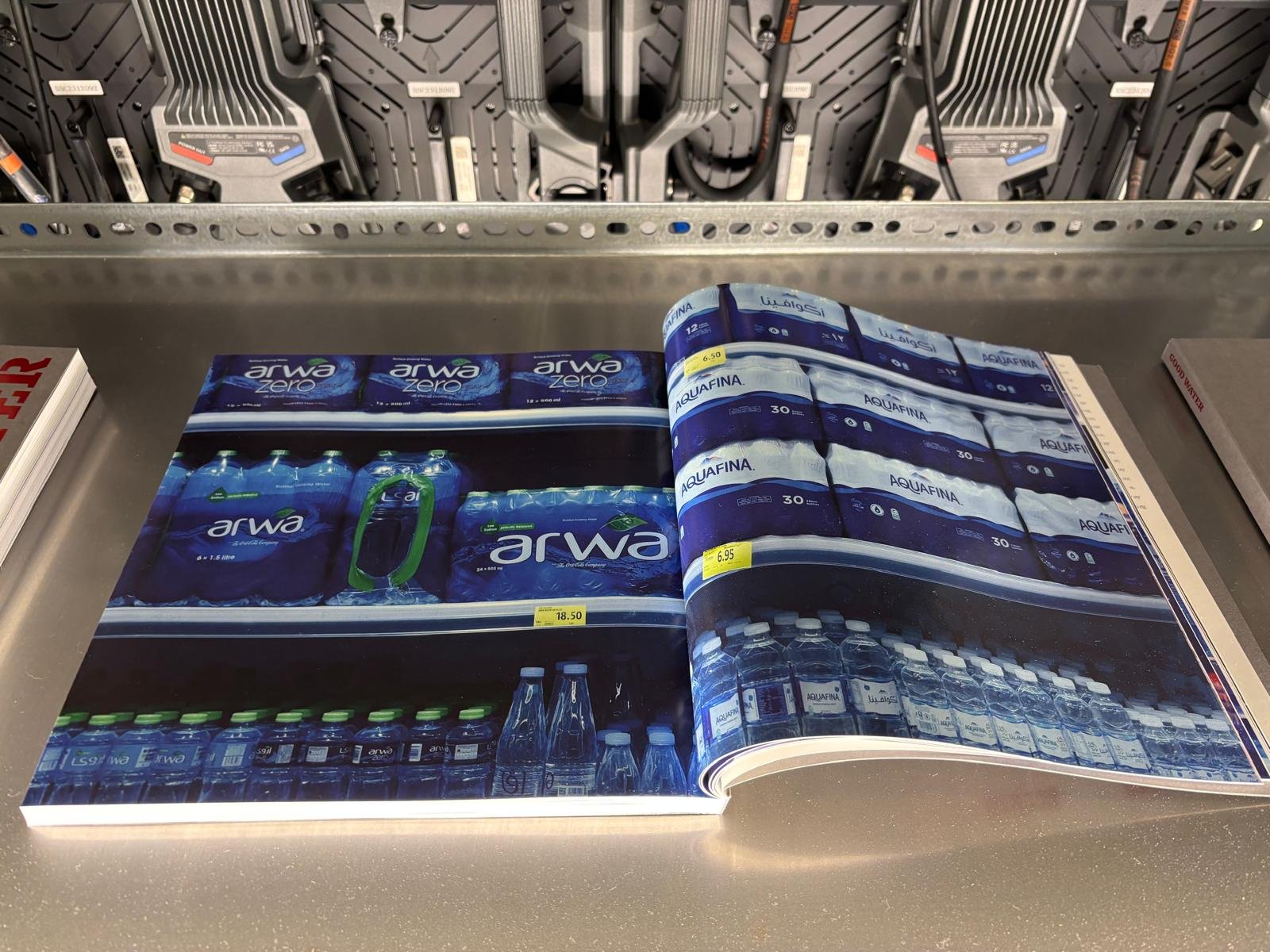

AT: The publication documents fifty examples of the Sabeel in context. Similarly to how insidious the passive use of water is, Sabeels are omnipresent in most [Saudi] cities, but no one notices them because they look like everything else and so are practically invisible in public spaces. By removing them from their respective contexts and relocating them here, we expose their significance and highlight the design of necessity. It’s a metaphor for the necessity of protecting water as a resource.

Dur Kattan: I also think it’s not just about the object of the Sabeel, but the system behind the water that arrives at the Sabeel. The installation videos also show the systems behind the designs: of the bottles, the factories, the infrastructure that allows water to flow freely and to be this “symbol of generosity.” This is about the whole design system of water; and the Sabeel is just our chosen representation of it.

DH: The material manifestation of these complex systems, I understand… so, the system itself becomes part of the critique?

DK: Exactly. The Sabeel is a representation of the broader water system — a visual manifestation of its complexity in one place.

AT: And it's simple to interact with: just a tap at the end. We take it for granted because we don’t see the infrastructure behind it. We don’t see what goes into play to make free water “free.” Someone somewhere bears the costs; so, it’s not really “free.” It’s free for the end consumer only. That’s why it’s so easy to take it for granted.

DH: Let’s speak about your use of materials. There’s a juxtaposition of polished and earthen textures, permanence, and ephemerality. How do your material choices reflect water infrastructure in arid Saudi landscapes? What role does materiality play in eliciting a physical response from the viewer?

FbN: The materials were contextual; not driven by aesthetics but by industrial standards. I don’t think there was an active decision in this regard. The industrial shift in Saudi Arabia brought stainless steel and aluminium, for example — materials that are easily produced, scalable, and practical — into common use. These materials are used for water because they also serve cooling and heating functions. We made a choice perhaps in terms of the scale of the pavilion; but the materials were inherent to the objects of the installation.

AT: One material that we did choose, though, is that of the water bottles. They resemble single-use plastic, but they’re not. That irony reflects the contradictions we wanted to highlight. We only made a few and we encourage visitors to take one. Once they run out, though, that’s it. We don’t have more. They’re replaced with compostable cups instead. This was very important for the installation.

DH: That appearance of plastic, but not its disposability, is a clever tension. Let’s talk about collaboration. You’ve worked together before. How did your individual practices inform this process? Were there moments of convergence or divergence?

DK: Aziz, who is also a part of the design team, is an artist. Fahad and Alaa are architects, designers, curators, and artists. I’m an artist but I also work in communication and public engagement. Our disciplines shaped everything: architecture, publication, interactivity. The whole thing was collaborative; and the multimedia aspects of the pavilion reflect this interdisciplinarity.

AT: And we’ve worked together before, so we already knew how to navigate the dynamic, which was already strong. There was always someone to steer the ship, so to speak…

DH: How long did it take to go from concept to execution?

AT: We’ve been working on this since October, though it did exist — in a sort of limbo — before that.

DH: Did you face any resistance when pitching the concept?

AT: No. Our commissioners were fantastic. We brainstormed a lot together and they’ve pushed us a lot. This is probably our eighth iteration. Same theme, different execution. It was challenging, but ultimately collaborative and very rewarding.

DH: Water is sacred and contested. It appears in religious texts and signals both ritual and scarcity. How does the installation engage with the temporality of water and Saudi Arabia’s future?

AT: The main takeaway for us is this: it’s not a scarcity issue; it’s a distribution issue. Water is hoarded by industries — for agriculture or cooling AI servers. When we began engaging with this issue, we also assumed it was a scarcity issue. The planet's water remains the same. Equity is the issue. The equity of distribution is the conversation we should all be having.

DH: Which aligns with topical AI ethics debates…

AT: Exactly. AI is embedded everywhere now but our entire team is from a generation where we only began engaging with AI at an older age. It’s normalized for future generations, though — AI will be second nature to them. The moral line here is blurry. Is it okay to use AI to soften an email? To write a research paper? To organize your daily schedule as a busy mother? It’s subjective.

DH: And literacy remains a challenge, especially in Arabic. AI language models are still limited.

AT: Yes. It’s embedded in every tool and website now. The question is not if we should use it – because it’s unavoidable – but how.

DH: By eliciting participation from your audience, your pavilion implicates them in the system it critiques. What strategies ensure that engagement is more than passive or performative?

AT: One observation that I’m happy with so far is that not everyone has been taking the water or picking up a bottle. Some hesitate, feeling a moral weight. That hesitation of seeing “free stuff” but not taking it just because it’s there is a meaningful one. Even with signs saying, “please participate,” people pause. That reflection is the point.

DK: Exactly. Even those who do take a bottle ultimately carry the message away with them.

DH: The bottles become, then, a form of micro-activism.

DK: Yes. Everyone contributes how they can. It’s not about judgement, but awareness. Allowing people to make their own decisions about how they interact with water.

DH: Let’s talk about continuity. In 2016, Saudi Arabia's inaugural Water Machine was a gumball dispenser of water, underscoring desalination and commodification. How does Good Water relate to that work? Is it a continuation or a recontextualization in light of current sociopolitical realities?

AT: Not a literal continuation, but it shows that the topic remains relevant a decade on. The players and themes have shifted — now it’s AI — but the core issue remains. Both projects disguise vast subjects in digestible formats, which suits the Biennale. But the two projects are unrelated formally. Living in landlocked Riyadh, where bodies of water are invisible (like the costs and structures we highlight), the theme of “water” resonates deeply.

DH: And what of the future of conscious design in Saudi Arabia?

FbN: It’s inevitable. Everything must now meet environmental certifications and sustainability protocols. It’s embedded in regulation.

AT: But like the water conversation, it begins with the individual. We can’t just rely on institutions. Earlier versions of the pavilion were more elaborate; but in the end, we brought it down to the essentials: a skeletal frame, a Sabeel, compostable bottles and cups that run out. These decisions started with us, the team, then extended to the commissioner — and hopefully they will ripple outwards. That’s how change begins.

DK: The deeper you dive into this subject matter, the more hidden costs you discover. It’s extremely complex.

AT: I will add, though, that it can almost feel impossible to solve the water issue globally. It often feels insurmountable because there are entire systems and governments that drive the issue. But individual action matters. There’s a lot that large entities can do to make a difference; but change can also begin with a person — or a small team.

End.